In cultivating this garden, we pause to acknowledge that the soil in which we sow and tend is located on the traditional and unceded indigenous lands of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Nation, situated on Turtle Island. We recognize and honor the enduring stewardship of the Haudenosaunee and all Indigenous peoples who have stewarded this land throughout generations.

As we cultivate the soil and celebrate the richness of biodiversity, we express gratitude for the ecological wisdom embedded in the cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples. In this garden, we aspire to integrate and respect traditional ecological knowledge, fostering not only a flourishing landscape but also a harmonious relationship with the land and its original caretakers.

The soil beneath our hands is more than just earth—it’s a canvas of cultural and ecological richness.

In this section, we will blend the principles of gardening for biodiversity with the wisdom shared by indigenous cultures. As we continue along this journey, our aim is to reconcile and reciprocate knowledge, weaving a narrative that goes beyond the usual textbooks and gardening guides. Join me in cultivating a garden that celebrates diversity, respects cultural nuances, and contributes to a harmonious relationship with the land and its stewards.

Why Incorporate Indigenous Knowledge?

- Indigenous practices are time-tested and tend to prioritize sustainability.

- It could enhance the health of your garden

- It opens up opportunities for partnerships, knowledge exchange, and a more inclusive gardening community.

- Indigenous knowledge is rooted in specific landscapes and ecosystems, and therefore could offer you more relevant and specific insight than you might find in books or other blogs.

“That’s the beauty of a thought, you can plant it, and it can grow with action”

-Skye Katsi’tsaronkwas Brooke Rice

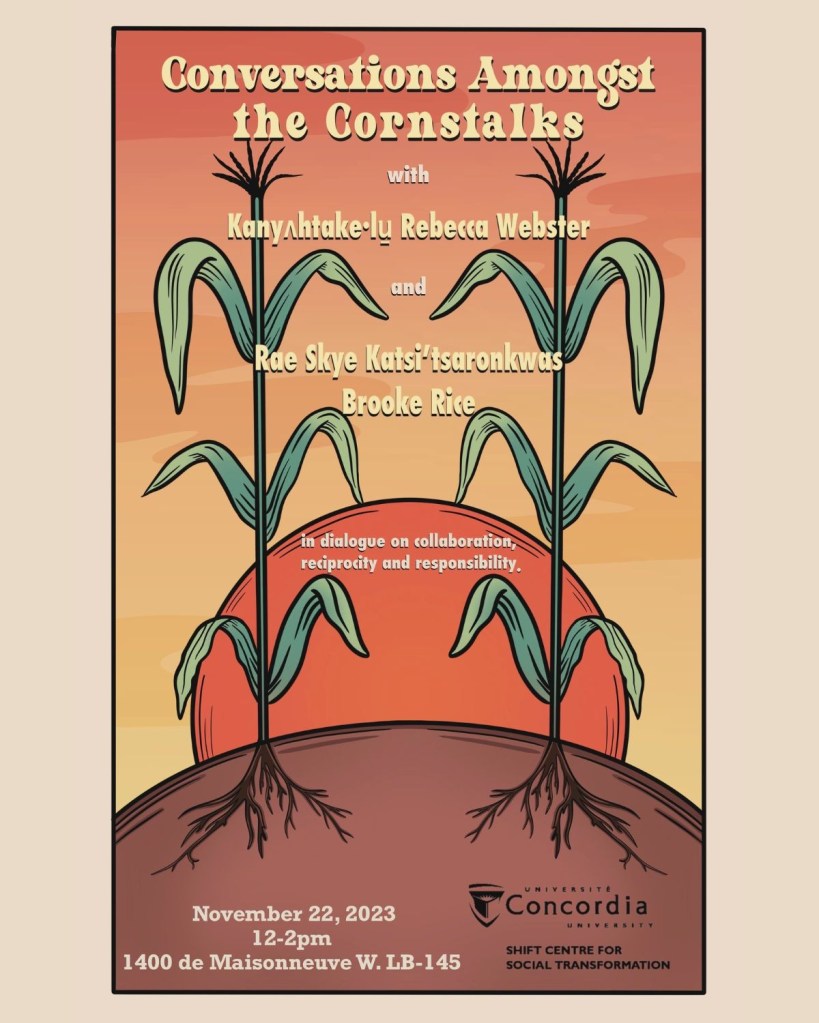

For context, It’s important to mention here that for this post I really wanted to get my knowledge straight from the source, so to speak, as direct engagement fosters a deeper understanding of cultural nuances that are often lost through written text. So, I searched far and wide for an opportunity that would allow me to gain a more personal hands-on experience… and then I read about an upcoming event called “Conversations Amongst the Cornstalks” and I knew this was my chance. Here, I was able to gain perspectives from not just one, but two separate indigenous tribes, all centered around the topic of communal gardening, ancestral food knowledge, seed saving, and creating a more holistic relationship with the world around us.

A bit about the main stars of the event…

Kanyʌhtake·lu̲ Rebecca Webster is an Oneida tribal citizen, seed saver and one of the members of Ohe·láku, a co-op of Oneida families that grow Iroquois white corn together.

Rae Skye Katsi’tsaronkwas Brooke Rice is one of the stewards of the Tka:nios project, bringing together intergenerational knowledge of food foraging, growing, harvesting and hunting to nourish the Kahnawake community’s connections with traditional foodways

The above poster and background of the guest speakers was taken directly from the promotional page for the event, please click here if you wish to have more info: https://www.concordia.ca/cuevents/offices/provost/shift/2023/12/22/conversations-amongst-the-cornstalks.html

Now, I could easily sit here and write an entire post just about all the incredible work these two women are doing, but I need to remind myself that we are here specifically for small scale gardening tips, so I will keep it narrowed down to just the three biggest take-aways.

1- Seed Saving

Let’s start with the basics.

Seed Saving is the act of preserving and storing seeds from one harvest in order to have seeds remaining for subsequent harvests1.

Heirloom Plants are old cultivars of plants, that are open-pollinated, and have not been hybridized or genetically modified in any way2.

Why plant heirloom seeds?

- They hold a genetic memory/code that has been mindfully selected for over many generations.

- To preserve genetic diversity– Industrialization of agriculture led to a decrease in varieties of plants being grown in favor of a select few that are easy to mass produce. Did you know that most of the bananas sold in the global west are genetically identical (clones)3?

- Because once lost, they are nearly impossible to get back- Like monocropping, having less genetic variety leaves our crops more vulnerable to disease and pest outbreaks– making them easier to lose4.

During the conversation between Brooke and Rebecca, they spoke strongly of the interconnectedness of the natural world. They emphasized the Earth, referred to as Our Mother, as both a provider and caretaker, underscoring the need for reciprocal respect, gratitude, and care towards her for the care she bestows upon us.

This perspective highlights the importance of heirloom seeds, portraying them not merely as resources, but as kin. The act of modifying these seeds is viewed not only as ethically wrong but also as a sign of disrespect to Our Mother, the ultimate creator of this precious lineage.

“Just like a woman’s body, only the middle of the corn is used for seed”

Kanyʌhtake·lu̲ Rebecca Webster

2- Composting and Fertilizer

Composting. What are our options? How the heck do you do it?

What should we use to fertilize our gardens?

Why avoid chemical fertilizers?

- They contribute to soil and water pollution through runoff5.

- They reduce soil health– chemical fertilizers cause nutrient imbalances, that affect soil fertility and long-term productivity6.

- They have adverse effects on beneficial insects and microorganisms in the soil, decreasing biodiversity7.

- Fertilizers can pose as a risk to human health both directly, and indirectly8

On this topic, Rebecca shared her perspective on soil fertility, explaining their community’s traditional practice of planting (by rule of thumb) about a half a fish in the soil with each Three Sisters crop bundle. This not only feeds the soil, but also reflects on our connection to the land, emphasizing reciprocity in the relationship with the earth. She also went on to mention the importance of natural-based methods of fertilization like manure and compost, not just as practical solutions, but as symbols of a commitment to sustainability and a harmonious coexistence with the natural world.

So, how can we care for the nutritional needs of our soil if we are limited by space?

- Vermicomposting- if you can commit, these little guys are actually quite easy to care for and is one of the cheaper options.

https://static.spokanecity.org/documents/solidwaste/recycling/2011-worm-composting.pdf

This is a great little guide for simple vermicomposting in a big ol’ Rubbermaid-type bin you might have lying around, but you can also buy a layered vermicomposting bin at any hardware store (RONA, Canadian Tire, Home Depot, etc.) - Outdoor Bin Composting- If you have a larger balcony or a small outdoor yard this is the method that requires minimal know-how.

There are two options for this route. First, a standard standing bin that you periodically open from the bottom and mix up the decomposing food scraps. Second, a tumbler bin that you turn instead of manually mixing. The second is probably better for balconies since they are elevated from the ground and produce less smell. - Bokashi Composting AKA compost tea- Another cheap method. Is easy to do once you get the hang of it, but does require some reading to understand the process.

For this you simply need a tall closed bucket with a spout attached to the bottom. You are essentially creating an anaerobic environment that your scraps ferment in, and the liquid from decomposition is drained out the bottom to make “compost tea” that you add to your water when watering plants. I have tried this method and my plants LOVED IT, my only complaint is that 1-2 buckets was enough for an entire growing season so it did not take care of my food scraps year-round.

https://www.planetnatural.com/composting-101/indoor-composting/bokashi-composting/ - Electric Composters- The quickest composting method, and requires the smallest amount of space and know-how. This method is by far the most convenient for apartment dwellers limited on space, but it comes with a heavy price tag.

These composters are generally countertop appliances you throw food scraps into, close the lid, press a button, and the next day your scraps are usable compost. While these appliances, in terms of life cycle analysis will never outcompete traditional methods, they are a great alternative when limited space doesn’t allow for large outdoor composting. - Community Composting– Not always available, but some neighborhoods with community gardens also practice community composting.

It’s worth checking out for your area. Here is a link for Montreal:

https://montreal.ca/en/how-to/find-community-composting-site

3- Mindfulness/Sharing is Caring

The last poignant topic Rebecca discussed was how her co-op garden was run. It was a perfect departure from traditional (by western sense) individual property rights, in favor of a community-centric approach. This solution functions through collective work, with harvest shares distributed equitably based on the amount of labor contributed by each member. Excess harvests are then set aside by the co-op and traded with citizens of their community in a simple barter system. A reminder to not only collaborate with the land, but with one another as well.

However, this view extends beyond human action to the very heart of the garden- the plants. Believing that the energy surrounding the plants influences the harvest, the community prioritizes positivity. They consciously avoid negativity or discord around the crops, recognizing that the vibes they impart to the plants find their way into the very food they cultivate. It’s a testament to the profound interconnectedness between the growers, the land, and the nourishment they collectively foster.

“The land remembers”

Kanyʌhtake·lu̲ Rebecca Webster

That being said, when you finish building your gardens, remember they are one small part of an entire ecosystem, just as you are. Your garden will be shared not just by you, but an entire community of diverse creatures. The birds will eat some, the squirrels will destroy what they can, but take what you need and leave the rest for nature and/or share with your neighbors and friends. Support your community. Share your seeds. But more importantly- share your knowledge as you grow and learn.

- https://www.firstnations.org/wp-content/uploads/publication-attachments/2015-Fact-Sheet-11-Seed-Saving-and-Seed-Sovereignty.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.westcoastseeds.com/blogs/wcs-academy/heirloom-heritage-seeds ↩︎

- https://www.wired.com/2017/03/humans-made-banana-perfect-soon-itll-gone/ ↩︎

- https://blogs.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/climatechange/Genetic%20diversity%20and%20interdependent%20crop%20choices%20in%20agriculture_heal%20and%20lubchenco%202004.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/environmental-implications-excess-fertilizer-and-manure-water-quality#:~:text=Some%20of%20these%20impacts%20include,and%20gases%20into%20the%20air. ↩︎

- https://e360.yale.edu/features/why-its-time-to-stop-punishing-our-soils-with-fertilizers-and-chemicals ↩︎

- https://e360.yale.edu/features/why-its-time-to-stop-punishing-our-soils-with-fertilizers-and-chemicals ↩︎

- https://amosinstitute.com/blog/the-health-impacts-of-chemical-fertilizers/ ↩︎

Leave a comment